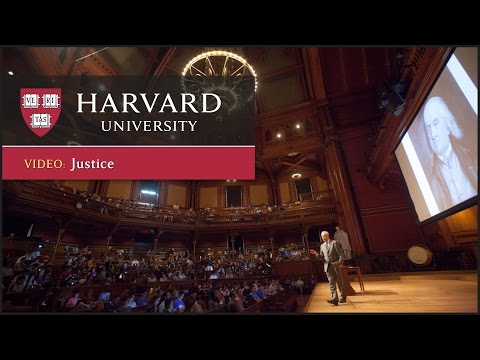

【哈佛名課─正義】謀殺的道德面? (Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 01 "THE MORAL SIDE OF MURDER")

VoiceTube 發佈於 2016 年 06 月 12 日  沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字- n. (c./u.)人;人們;人們;家人;員工

- v.t.居住

- n. pl.人們

- n.違法;犯罪

- adj.不道德的;犯罪的;不適當的;錯誤的;錯誤的;不對的

- v.t.冤枉;委屈

- n. (c./u.)車;汽車;(火車)車廂;電梯轎廂;賽車;纜車

- n. (c.)骰子;螺絲沖模

- v.i.壞掉;失去作用;消逝;死亡

- v.t.用模具沖壓;渴望