字幕與單字

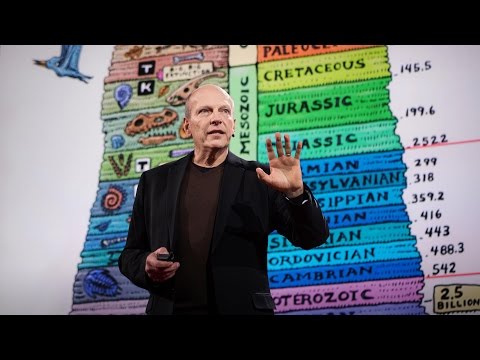

TED】肯尼斯-拉科瓦拉。獵殺恐龍讓我知道了我們在宇宙中的位置(獵殺恐龍讓我知道了我們在宇宙中的位置|Kenneth Lacovara)。 (【TED】Kenneth Lacovara: Hunting for dinosaurs showed me our place in the universe (Hunting for dinosaurs showed me our place in the universe | Kenneth Lacovara))

00

g2 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能