字幕與單字

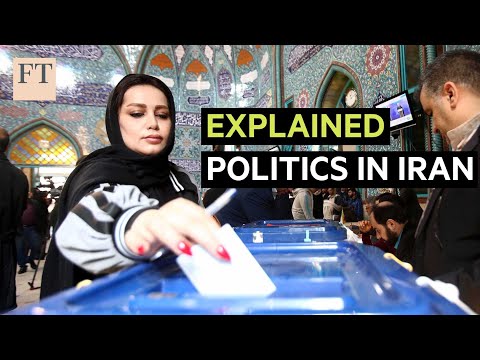

伊朗強硬派為何贏得議會選舉? (Why Iran's hardliners won parliamentary elections | FT)

00

林宜悉 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

general

US /ˈdʒɛnərəl/

・

UK /'dʒenrəl/

- adj.一種常見的做法,整體;籠統的;廣泛適用的;總指揮的

- n. (c.)將軍

- n. (c./u.)大眾;一般研究領域

A1 初級多益初級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能