字幕與單字

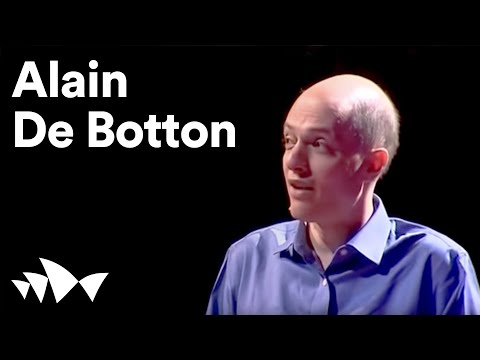

阿蘭-德波頓--《無神論者的宗教》(《思想之家》) (Alain De Botton - Religion For Atheists (Ideas at the House))

00

孫子文 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

to

US /tu,tə/

・

UK /tə/

- adv.指向…點;至

- prep.附屬、連接的介係詞;比較的介係詞;指向;給予的介係詞;對…的反應;(用於動詞前;表示不定式);到…範圍;到;表達;放在動詞後的介係詞;去;然後;…和…;向;朝(某方向);(表示時間)直到...;聽的介係詞

- particle(不定詞)

A1 初級初級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能