字幕與單字

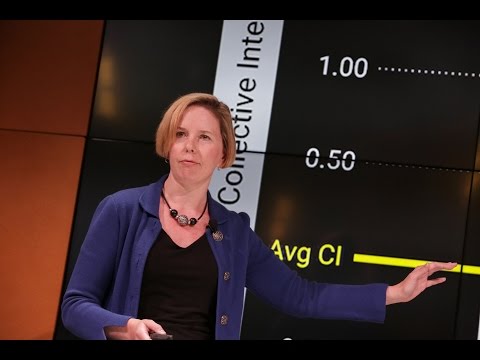

是什麼讓一個團隊比另一個團隊更聰明? | 卡內基梅隆大學,安妮塔-威廉姆斯-伍利。 (What makes one team smarter than another? | Anita Williams Woolley, Carnegie Mellon University)

00

Penny 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

average

US /ˈævərɪdʒ, ˈævrɪdʒ/

・

UK /'ævərɪdʒ/

- n. (c./u.)平均

- v.t.算出...的平均數

- adj.平均的;一般的,通常的;中等的

A2 初級多益中級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能