字幕與單字

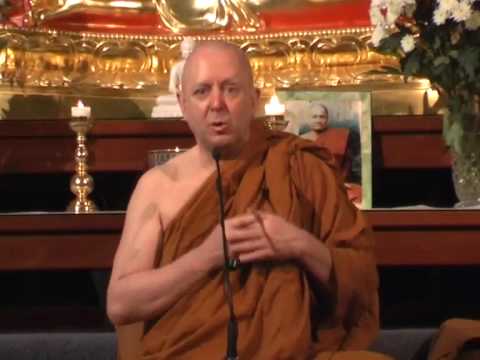

如何做個積極的人|Ajahn Brahm著 (How To Be Positive | by Ajahn Brahm)

00

Buddhima Xue 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

time

US /taɪm/

・

UK /taɪm/

- n. (u.)節拍;(準確的)時間;時間(多寡);(經歷的)一段時光;(經歷的)時光;時代;時期;時間;時刻;時候

- v.t.測量(節拍);為...計算時機;計時;測量時間;使適時;安排...的時間

A1 初級多益初級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能