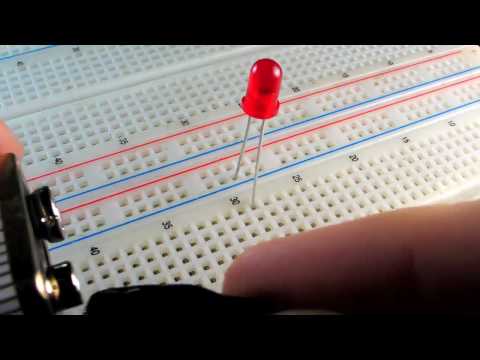

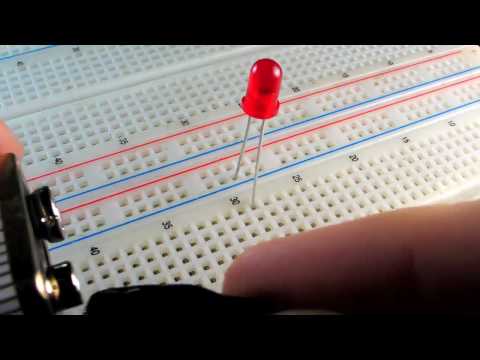

MAKE呈現。LED (MAKE presents: The LED)

Sea Monster 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日  沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字US /ˈnɛɡətɪv/

・

UK /'neɡətɪv/

- n.負電極的;否定詞;否定句;底片

- adj.消極的;負的;負面的;否定的;陰性的;負電的

US /ˈpɑzɪtɪv/

・

UK /ˈpɒzətɪv/

- adj.積極的;建設性的;確定的;正極的;積極的;有利的;陽性的;樂觀的;正數的;正像的

- n.正片

- n. (c./u.)鉛線;線索;主角;鉛;導線;領先

- adj.主演的

- v.t.帶領;(在比賽中)領先

- v.t./i.帶路

US /ɪkˈspɛrəmənt/

・

UK /ɪk'sperɪmənt/

- n. (c./u.)實驗;嘗試

- v.t./i.進行實驗;進行試驗