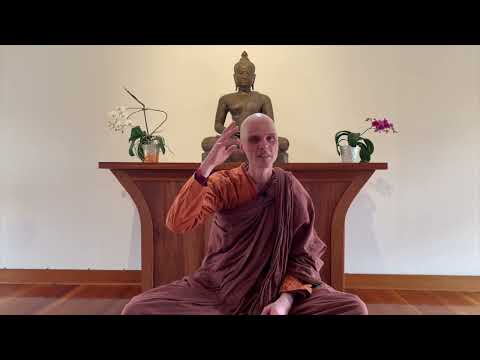

比丘阿那律 | 體悟心性 | 2020 年 4 月 (Bhikkhu Anālayo | An embodied mindfulness | April 2020)

Mook 發佈於 2024 年 08 月 26 日  沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字US /æŋˈzaɪɪti/

・

UK /æŋ'zaɪətɪ/

- n. (u.)焦慮 ; 掛慮 ; 不安 ; 渴望 ; 熱望 ; 焦慮渴望 ; 焦急 ; 擔憂 ; 慮 ; 悒

US /pəˈtɛnʃəl/

・

UK /pəˈtenʃl/

- adj.可能的;潛在的;潛在的

- n. (u.)潛力,潛能

- n. (c./u.)潛力;潛能;潛在候選人;勢

US /pɚˈsɛpʃən/

・

UK /pəˈsepʃn/

- n. (c./u.)知覺;感知;知覺;理解;看法;觀點;信念;洞察力

US /ˈæspɛkt/

・

UK /'æspekt/

- n. (c./u.)方面;觀點;(某物的)要素;特徵