字幕與單字

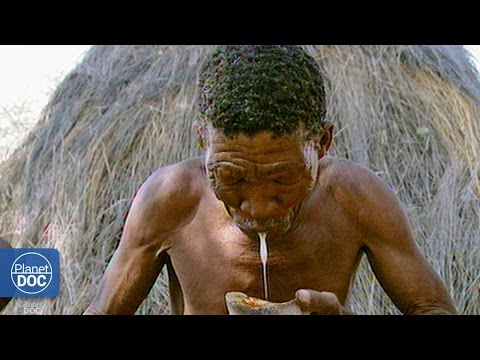

骷髏沙漠完整的紀錄片|Planet Doc 完整的紀錄片 (Desert of Skeletons. Full Documentary | Planet Doc Full Documentaries)

00

realvip 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

territory

US /ˈtɛrɪˌtɔri, -ˌtori/

・

UK /'terətrɪ/

- n. (c./u.)領土;地盤;(行動;知識等的)領域;範圍;領土:版圖;領土;版圖;職權範圍;銷售區域;勢力範圍

B1 中級多益中級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能