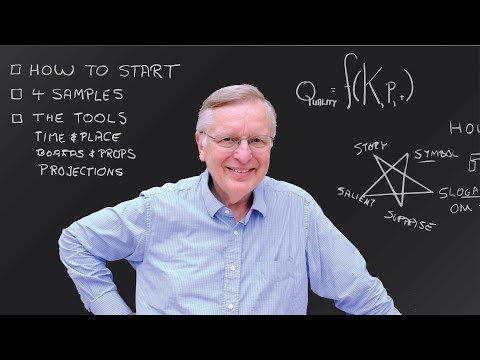

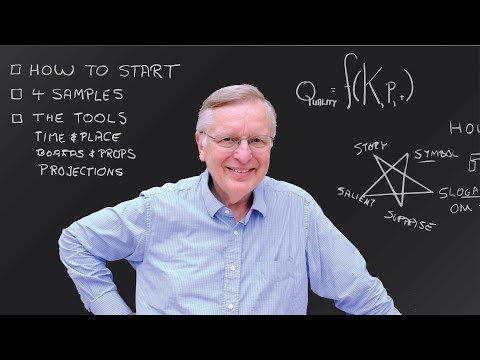

帕特里克-溫斯頓的《如何說話 (How To Speak by Patrick Winston)

沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字US /ˈrek.əɡ.naɪz/

・

UK /ˈrek.əɡ.naɪz/

- v.t.認可;接受;賞識;承認;表彰;嘉獎;認出,認識

US /ˌɑpɚˈtunɪti, -ˈtju-/

・

UK /ˌɒpə'tju:nətɪ/

- n. (c./u.)機會;時機;良機;工作機會;商機

US /ˈpræktɪs/

・

UK /'præktɪs/

- n.(醫生;律師等的)業務;工作;練習;慣例

- v.t./i.(醫生;律師等)開業;實踐;練習;操練;實踐