字幕與單字

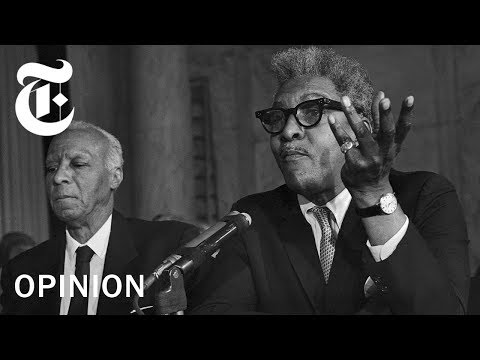

為什麼一個同志、黑人民權英雄反對平權行動|紐約時報評論 (Why A Gay, Black Civil Rights Hero Opposed Affirmative Action | NYT Opinion)

00

林宜悉 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

discipline

US /ˈdɪsəplɪn/

・

UK /'dɪsəplɪn/

- n. (c./u.)紀律;訓服;學科;懲罰(某人);自律

- v.t.訓練(某人)使其馴服;懲罰(某人)

B1 中級多益中級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能