字幕與單字

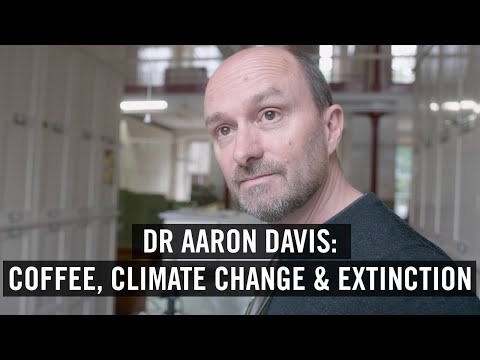

咖啡、氣候變化與滅絕。在邱園與Aaron Davis博士對話 (Coffee, Climate Change & Extinction: A conversation with Dr Aaron Davis at Kew)

00

林宜悉 發佈於 2021 年 01 月 14 日收藏

影片單字

potential

US /pəˈtɛnʃəl/

・

UK /pəˈtenʃl/

- adj.可能的;潛在的;潛在的

- n. (u.)潛力,潛能

- n. (c./u.)潛力;潛能;潛在候選人;勢

A2 初級多益中級英檢

更多 使用能量

解鎖所有單字

解鎖發音、解釋及篩選功能