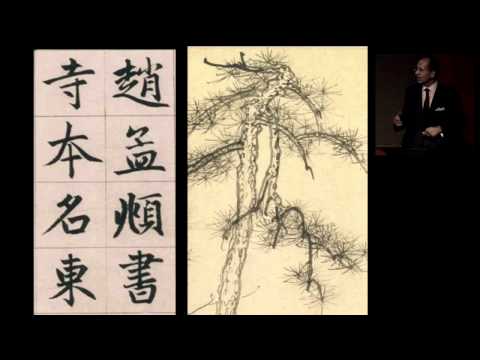

忽必烈汗的世界繪畫革命 (The World of Khubilai Khan: A Revolution in Painting)

Ashely Ma 發佈於 2024 年 09 月 14 日  沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字US /ɪkˈstrɔ:rdəneri/

・

UK /ɪkˈstrɔ:dnri/

US /ˌɪndəˈvɪdʒuəl/

・

UK /ˌɪndɪˈvɪdʒuəl/

- n. (c.)個人;單個項目;個體;個人賽

- adj.個人的;獨特的;個別的;獨特的

US /sɪɡˈnɪfɪkənt/

・

UK /sɪgˈnɪfɪkənt/