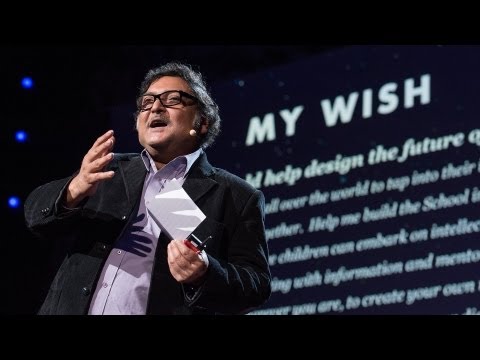

【TED】Sugata Mitra: 建立雲端的學校 (Sugata Mitra: Build a School in the Cloud)

VoiceTube 發佈於 2013 年 04 月 05 日  沒有此條件下的單字

沒有此條件下的單字- v.t./i.學習 ;得知

- n. (u.)學習(的動作);學習;學識

- adj.學習的

US /kəmˈpjutɚ/

・

UK /kəmˈpju:tə(r)/

- n. (c.)魚群;海生動物群;學校;學院;學派;流派

- n. (u.)學校

- v.t.教育、授課

- adj.學校的

- n. (c./u.)人;人們;人們;家人;員工

- v.t.居住

- n. pl.人們